#GeneracionBicentenario Pt. 1: The threat

By Julia M. Hodgins

Abstract:

This two-part article analyzes the protests that happened in Peru between November 9-16 2020. In this first segment, Julia M. Hodgins reviews the political development of impeaching President Martin Vizcarra, led by the unpopular Congress, that fractured the democratic order turning the state into the enemy of its own population.

On Monday November 9th 2020, the Peruvian Congress massively voted (107/130) in favor to impeach President Martin Vizcarra under vacancy due to permanent moral incapacity, induced by an investigation following accusations of corruption against him. Allegations state that Vizcarra received bribes (“coimas”) years back when he was Regional Governor of Moquegua, claims are still to be proved. Interestingly, in October 2020 Vizcarra’s popularity rose to 54% according to a survey from IPSOS [1] while that of the congress was 32%; and, 78% of Peruvians thought that Vizcarra should complete his mandate and face justice after that.

Since July 28, 1821, Peru is a constitutional republic. Currently, in words of Javier De Belaunde – lawyer expert in constitution law – it is a ‘presidentialist’ [2] regime, meaning that the figure of the President is protected to guarantee political stability and continuity until the following election. The Constitution – Peruvian Magna Carta– allows impeachment only for treason, impeding elections, precluding the Congress functions, precluding functions of other essential powers and instances [3]. Any crime (or allegations) committed before the mandate, or wrongdoings during it, shall be prosecuted only after a sitting president’s electoral defeat; pertinent regulations and provisions secure the prosecution.

Concomitantly, the Peruvian constitution (article 113, number 2) states [4] that the president can be removed from office only after the Congress declares him/her as “Permanently Incapacitated physically and morally” pointing to ability to function. The ambiguity of this qualification led to Vizcarra being declared “permanently morally incompetent” to govern Peru due to crimes, despite those are not proved yet. The president of the Congress, Manuel Merino, following protocol designated himself as Transitory President of Peru and formed a new cabinet.

Alfredo Villavicencio [5], Dean of the Law School in Pontifical and Catholic University of Peru – one of the most prestigious law schools in the country – published a statement on November 10, qualifying the interpretation of permanent moral incapacity made by the Congress as isolated and arbitrary, leading into a power display that is anti-juridic (“irresponsible and disproportionate”). Villavicencio adds that the Congress has broken the principle of separation and balance between powers, that cements democracy, by going beyond its competence when acting as a sanctioning entity. According to Barry Buzan, this impeachment would constitute a threat to the state and the nation [6], as it suggests a political move, not a moral or judicial one, which destabilizes the country. Peru is already strained by the healthcare crisis of the pandemic and its correlated devastating effects deriving in an economic downward spiral [7].

The confrontation

Controversy was sparked, along with the question of why now if in eight months accusations against Vizcarra would have been processed anyway? How could a Congress with sixty-eight [8] representatives having civil and penal cases in court consider Vizcarra morally incompetent, when accusations against the latter have not yet been proved? Why to impeach a president five months before elections? Recent developments revealed potential drivers: ongoing electoral and educational reforms were threatened to be rolled back [9], and a twenty-year concession contract was given to a telecommunication company without following regular procedures.

What makes this protest worth the attention? David Kilcullen contends that irregular warfare happens online and in urban settings [10], emphasizing that mutual informing of those domains is key to the articulation and sustainment of the operation; evidence abound in this case. As soon as the news broke Peruvians in the country and abroad turned to social networks, sharing thoughts, and expressing their rejection with hashtags [11] like #merinonoesmipresidente (“Merino is not my president”), #FueraMerino (Merino Out), #FueraCongresoCorrupto (Out corrupt congress), #ElCongresoNoMeRepresenta (The Congress does not represent me), #NoEsPorVizcarra (This is not about Vizcarra). Intensity of these sentiments reactivated the hashtag #tomalacalle (Occupy the streets) – used in 2013 to protest against the juvenile labour law – later adding #tomatuparque (Occupy your park, Figure 1) as protests decentralized to other areas of Lima, and multiplied over the national territory and abroad (Figure 2).

TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, and even LinkedIn became the common spaces of expression, communication, coordination, and support. This exchange facilitated the articulation of marches under the lead of Millennials who cell-in-hand shaped a citizenship awakening, arguably the largest surprise of the protest as this group is assumed as disengaged, individualistic, distracted. The lack of a caudillo, leader, or political party heading the protests supports the argument.

What is now called the Generation of the Bicentenary has capitalized on learning from protesting experiences in Chile (2019), United States (2020), and Hong Kong (2018-ongoing), as Alexandra Arana Blas depicts in the second part of this article. In nanoseconds and within the hallways and rooms of the world they know better, cyberspace, they shaped the most massive civic event Peru has seen in decades, taking care to comply with Covid-19 safety protocols and assuring to be peaceful, see figure 3. The movement reflected into homes as people made protesting noise, time-synchronized, by hitting a cooking pot in what was called the “cacerolazo,” practice traced back to 2001 when Argentinians took Fernando de la Rua out of office.

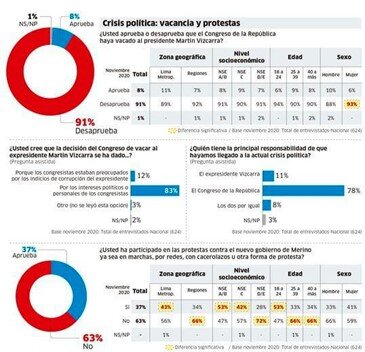

Another remarkable feature is that the protest engaged citizens from diverse population sectors in a country extremely divided by inequalities. A survey from the Institute of Peruvian Studies [12] of the Pontifical and Catholic University of Peru reports that, 37% of interviewees confirmed to have protested either in the street marches, online, the “cacerolazo” or other, superior to the regular 14% registered in the country before, see figure 4. Noteworthy, seeing most of socio-economic sectors actively engaged signals common sentiments about the de-facto regime, congruent with the 91% disapproving to the deposition of Vizcarra, the 78% blaming the Congress for the political crisis, and 83% considering the driver to be personal and political agendas of Congress members. After six days – and the death of two protestors – the civilian movement puzzled the de-facto government, forcing Merino’s resignation on Sunday November 15, 2020 [13].

Two fanpages called the attention, “Peruanos en el Mundo en Defensa de la Democracia” [14] (Peruvians Abroad in Defense of Democracy) where pictures, videos, and messages rejecting the destitution were posted non-stop from many cities worldwide. A second one “Apoyo a manifestantes peruanos” (Support for Peruvian protestors – Figure 5) sharing information about safety and security protocols for protestors, free legal representation for those detained, updates from the volunteer medical brigades attending injured protestors, and resources of all sort. Later, this page became private as it transpired that a member was arbitrarily detained at home for offering to print posters, suggesting cyber espionage, see Figure 6. At the moment, the page shows as archived.

Protesting and gathering for that is a constitutional right in Peru, clearly violated by spying and detaining citizens. Also, on the crucial night, Saturday November 14, streetlights and access to cell networks were turned off in Plaza San Martin Central downtown Lima, main location of the marches. Under that darkness two working students were killed by police and about a hundred were injured with diverse severity, pointing to the threat posed by the state to its own population, in a confrontation where the first uses weapons against the second, which – according to Benjamin Miller – arguably constitutes an internal security matter [15]. Miller adds that internal threats can spill beyond borders, evidenced here when Anonymous hacked web sites of the Congress and the Police [16], and the hashtag #peruvianlivesmatter trended showing international support, figure 7.

Merino’s de-facto regime might have miscalculated the population’s weariness with corruption and political instability, which does not subtract the arguments above. Rather, it shows strategic poverty, lack of leadership in the Congress, and profound disconnection between political class and people, which ultimately delegitimizes a government in democracy. The coup disguised as impeachment became an internal security matter, which stoke a population bored of rapacious authorities that spontaneously articulated an irregular warfare response led by Millenials.

About the author

Julia Hodgins

MA candidate in International Affairs at King’s College London, holds a BA-Honors in Sociology concentrated in Social Research. Julia is a volunteer radio producer, an active member of feminist collectives, and a Research Intern focused on Culture, Society, and Security with ITSS Verona (International Team for the Study of Security). Her interests are social equality, decolonization, gender security, and strategy. A fervent cat-o-holic.

References:

[1] IPSOS, National Survey Peru, October 2020, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-10/la_gestion_publica_octubre_2020_-_encuesta_de_opinion_el_comercio-ipsos.pdf, 11

[2] Alberto De Bealunde interviews Javier De Bealunde, Instagram November 20, 2020 https://www.instagram.com/tv/CHy2vrypEoV/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

[3] Ibid

[4] Constitución Política del Peru, accessed November 24, http://www.pcm.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Constitucion-Pol%C3%ADtica-del-Peru-1993.pdf

[5] Facultad de Derecho PUCP, November 10, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/FacultaddeDerechoPUCP/posts/3419570461413144

[6] Barry Buzan, People, States & Fear (2nd edition). Colchester: ECPR Press, 2007) EBook Proquest, 109

[7] Jonathan Castro, “El congreso peruano hundió a un presidente desinteresado en el juego político,” The Washington Post, November 11, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/es/post-opinion/2020/11/11/martin-vizcarra-presidente-peru-destitucion-crisis/

[8] As, November 10, 2020, https://peru.as.com/peru/2020/11/10/actualidad/1605028028_089256.html

[9] Gestion, “Telesup retira carta que exige a Sunedu acatar cautelar para anular denegatoria de licenciamiento,” Diario Gestion, November 12 2020, https://gestion.pe/peru/telesup-retira-carta-que-exige-a-sunedu-acatar-cautelar-para-anular-denegatoria-de-licenciamiento-sunedu-nndc-noticia/. And, Milagros Campos, “Perú: reforma política y elecciones,” Politica Exterior, July 28, 2020, https://www.politicaexterior.com/peru-reforma-politica-y-elecciones/

[10] David Kilcullen, “Counter-insurgency Redux,” Survival 48, no. 4 (2006), DOI: 10.1080/00396330601062790: 113-114

[11] UNDiario.pe https://undiario.pe/2020/11/13/jovenes-protagonizan-protesta-nacional-se-han-metido-con-la-generacion-equivocada

[12] Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, “IEP Informe de Opinión – November 2020, https://iep.org.pe/noticias/encuesta-de-opinion-octubre-2020/, 11-13

[13] BBC News, Mundo, November 15, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-54953923

[14] Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/Peruanos-en-el-Mundo-en-Defensa-de-la-Democracia-109624850959792

[15] Benjamin Miller, “The Concept of Security: Should it be Redefined?” Journal of Strategic Studies 24, no. 2 (2001), ProQuest Ebook: 21

[16] Archyde, “Five days after Vizcarra’s removal, Anonymous hacked the website of the Peruvian Congress”, November 15, 2020, https://www.archyde.com/five-days-after-vizcarras-removal-anonymous-hacked-the-website-of-the-peruvian-congress/