#GeneracionBicentenario Pt. II: Fan Culture and Politics

This two-part article analyzes the protests that happened in Peru between November 9-16 2020. In this second segment, Alexandra Arana-Blas narrates the Millenials’ intervention from the perspective of one of its actors, who reviews iconography and messages under Fan Theory and political activism, arguing that Peruvian Millenials are engaged citizens whose popular culture feeds their social and political stand.

Young people of the Millennial Generation and Generation Z, especially those of us born after September 12, 1992 [1] ¾the year in which Abimael Guzmán was captured [2] ¾ have grown up with phrases such as “Why do you talk about the Conflicto Armado Interno (Internal Guerrilla) if you were not even born then?”; “Don’t criticize Alberto Fujimori or the Armed Forces. They have saved us”; “You don’t know what we have suffered” or “In a war, deaths are necessary”. This contempt for our critical capacity, as well as the disdain for our ability to empathize with history, stories, and testimonies caused dissatisfaction amongst us.

This contempt and under-estimation for our reflective capacity ¾perhaps, with the aim of preventing us from questioning the official history and reliving the wounds caused by the social, political, and economic crises – coupled with the criticism we have received for prioritizing recreational activities such as entertainment and the consumption of fantasy books, mangas, TV series, cartoons, anime and video games, made many believe that ours was an apolitical generation [3]. However, in recent days we have shown on the social networks and in the streets that what is personal is also political.

Young people ¾especially those in urban areas and with access to the Internet¾ have witnessed large mobilizations in recent years such as those in Hong Kong, the United States, and Chile. From the first, we learned defense tactics and mobilization strategies in a context of repression [4]; from the second, the possibility of demonstrating in networks and thereby preventing them from being another tool of surveillance and oppression [5]; and the third, the possibility of making protests a space for recreation and resistance [6].

This is how we, in the protests in the streets and networks between November 9 and 15, have expressed to never return to the times of dictatorship and political instability. Also, through the spontaneous generation of these movements, we reaffirm our disconnection to the terrorist extreme of the leftist parties.

Our knowledge of the networks has allowed the emergence of various forms of activism: from sharing statements in fast speed to the appearance of groups that shared information about police repression. The information was abundant, and it was quickly corroborated by collaborators and participants. These alternative media channels have been more reliable and trustworthy than television channels and official media, which, as the days progressed, downplayed if not avoid broadcasting content about the marches.

But what attracted most of the attention was the participation of fandoms in the protest. Otakus and K-pop fans denounced the Twitter accounts of politicians, journalists, and the State itself, and intervened the networks and social media profiles of various authorities using hashtags in conjunction with images of K-pop artists such as BTS (Picture 2), Black Pink (Picture 3), TWICE, among others. This use of hashtags and images intends to spam and distract the original purpose of the intervened post. Similar tactic applied to the hashtag #TerrorismoNuncaMas (TerrorismNeverAgain), which objective from the official end was to delegitimize our peaceful marches, was reappropriated by fandoms and transformed into a space of resistance.

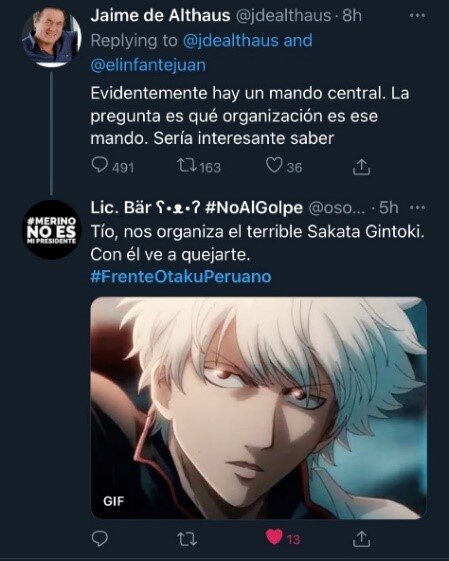

But unlike other countries, where the online protest was exclusively attributed to K-pop fans, in Peru we have seen the participation of otakus or anime fans. Picture 4 is an evidence where a user re-signifies multiple hashtags – supporting the coup and aiming to delegitimize the protests – though the use of an anime image.

Similarly, Picture 5 is a form of direct intervention on the wall of journalists and politicians who were in favour of the coup, intending to attribute responsibility of the spontaneous marches to a particular political group. In this example, as a satire, the organization of the protests was attributed to an anime character, along with the hashtag #FrenteOtakuPeruano.

Along with this mobilization in networks, there was also the creation of various groups, such as the “Frente Otaku Peruano” ("Peruvian Otaku Front"), whose statements sought to create a critical and inclusive community that invites the formation of a citizen consciousness. In Picture 6, dated November 12, 2020, the “Frente Otaku Peruano” posted the following statement:

“#FrenteOtakuPeruano es un espacio para que los otakus peruanos unamos fuerzas para hacer frente al golpe de Estado que inició el lunes 09 de noviembre.” (PeruvianOtakuFront is a space where Peruvian Otakus join forces to confront the Coup-de-etat that started on Monday November 9.)

#MerinoNoEsMiPresidente (MerinoIsNotMyPresident)

#EsteCongresoNoMeRepresenta (ThisCongrerssDoesNotRepresentme)

#FrenteOtakuPeruano” (PeruvianOtakuFront Facebook)

The post introduces a ludic element: an image of a female anime character ¾Mugi, from the series K-On! – as president of Peru. The statement invites resistance against the coup d’etat, as well as union in a fandom that until before the protests in Chile ¾where otakus went to protest dressed as their favorite manga and anime characters, and sang Digimon songs¾ did not seem to have a political consciousness, or link their fan identity with citizenship.

Along the same lines, the PeruvianOtakuFront released what is, to date, its most recent statement. Dated on November 18, 2020, three days after the death of two young people were announced, resulting from police violence, it says (Picture 7):

“Today, November 18, 2020, we have a new president and soon new cabinet will take the oath. But we should remain vigilant.”

#FrenteOtakuPeruano #Otakudō” (PeruvianOtakuFront, Facebook)

The statement on Fig. 7 lacks accompanying images, the text is deep and more developed as compared to the earlier one. These features show the intense mark that events – that happened when Bryan and Inti were killed – have left on the young people who protested in the streets and the social networks. Likewise, the statement calls for hope and calls on anime fans to combine their taste for fiction with social reality.

In addition to participating in networks, the otaku community protested in the streets through banners, the use of costumes, symbols, and elements of their favorite manganimes (Picture 8, Picture 9 and Picture 10) [7], [8]. With them, other communities participated such as potterheads (Picture 11), and gamers (Picture 12).

The mobilization of different groups of fans not only shows a dissatisfaction and weakening of the political class, which seem to no longer respond to the concerns of young people; these marches also proved that fan culture has great articulation. And in the case of otakus and potterheads, their posters evidence (Picture 9, Picture 10, Picture 11) that fiction is a space that allows the creation of an “utopian hope” [9]. In other words, the themes that both the manganime and the Harry Potter novels address allows their readers to create critical judgment and play an active role in seeking social change.

Finally, as a young woman who participated in the protests said, "We are the generation that does not drop bombs, but deactivates them". In that sense, fiction and fan culture have allowed us to build a critical conscience, where we make our voices heard in a peaceful way aiming to not repeat either days of dictatorship or terrorism.

About the author

Alexandra Arana-Blas

Teaching Assistant of the Academic Research course at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú where she got a BA in Hispanic Literature. Studied at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Germany. She is currently editor at the electronic magazine Proyecto Sugoi. Her interests are queer and gender theory, LGBT studies, Asian studies, and pop culture (anime and manga. Received the Academic Research Award PUCP (2012-II) and the Premio PADET (2016).

references:

[1] Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación [CVR]. “Capítulo 5 PCP–SL 1992-2000”. Informe final. Tomo II: Los actores del conflicto. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/pdf/TOMO%20II/CAPITULO%201%20-%20Los%20actores%20armados%20del%20conflicto/1.1.%20PCP-SL/CAP%20V%20SL%201992-2000.pdf

[2] Abimael Guzmán Reinoso, known as Camarada Gonzalo, was the founder and leader of the Partido Comunista del Perú – Sendero Luminoso (PCP–SL) [Peruvian Communist Party – Shining Path]. It “is a subversive and terrorist organization that, in may 1980, unleashed an armed conflict against the State and Peruvian society. The CVR has verified that throughout this conflict the most violent of the history of the Republic, the PCP–SL committed very serious crimes that constitute crimes against humanity and was responsible of 54% of fatalities reported to the CVR […] 31,331 people” [my translation]. “Chapter 1 PCP–SL Origin”. Final Report. Tome II: The actors of the conflict. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/pdf/TOMO%20II/CAPITULO%201%20-%20Los%20actores%20armados%20del%20conflicto/1.1.%20PCP-SL/CAP%20I%20SL%20ORIGEN.pdf

[3] Matt Hills. Fan Cultures (Nueva York: Routledge, 2002).

[4] Rory Byrne. “New Protest Tactics in Hong Kong”, Medium, August 28, 2019. https://medium.com/@roryireland/new-protest-tactics-in-hong-kong-674ae256af1

[5] Shreyas Reddy. “K-pop fans emerge as a powerful forcé in US protests”, BBC News, June 11, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52996705

[6] RPP Noticias. “Los otakus se unen a las protestas en Chile con la canción de Digimon y Naruto como símbolo”, RPP Noticias, October 25, 2019. https://rpp.pe/tecnologia/redes-sociales/chile-twitter-viral-otakus-se-unen-a-las-protestas-en-chile-con-la-cancion-de-digimon-y-naruto-como-simbolo-noticia-1226596

[7] RPP Noticias. “‘La revolución será otaku o no será’: Los ingeniosos carteles de anime durante las protestas ciudadanas en Perú”, RPP Noticias, November 13, 2020. https://rpp.pe/tecnologia/redes-sociales/marchas-la-revolucion-sera-otaku-o-no-sera-los-ingeniosos-carteles-de-anime-durante-protestas-ciudadanas-en-peru-manuel-merino-noticia-1304112

[8] The question remains open as to whether or not the protestants performed a cosplay. It must be taken into account that the majority attended the marches with costumes, symbols and elements of the manganime, but for this reason there was not a complete personification nor did they act like the characters, which is essential for cosplay

[9] “Rita Felski ascribes a potential to fiction often dismissed as ‘melodramatic’ or ‘escapist’ […] their negation of the everyday may hold a powerful appeal for the disenfranchised groups […] such fiction may provide some ‘utopian hope’ necessary for political action”. Turning Pages. Reading and Writing Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2006), 23.